Sites > Goodwin Sands

Site: Goodwin Sands - Dredging

Techniques: Geophysics, Site Assessment

|

Dover Harbour Board (DHB) is proposing to dredge over 2 million cubic metres /3 million tonnes of sand and gravel from the historically-important South Goodwin Sands for their Dover Western Docks Revival development.

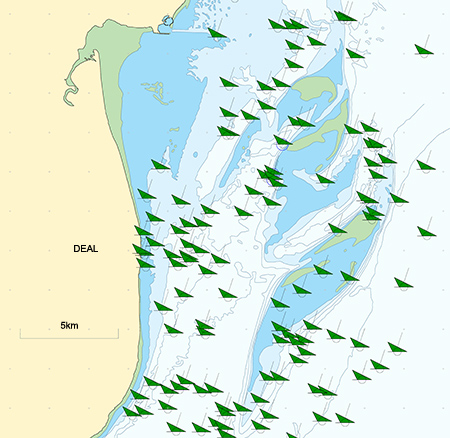

The Goodwin Sands are located off Kent in the south-east of England, three miles off the coast from the town of Deal (see Fig. 1). The sands lie in the narrowest part of the English Channel and rise from the depths to partly dry out at low water - this is one of the most treacherous stretches of water in Britain. The Sands lie in the busiest shipping lane in the world and have always been a hazard to navigation since ships began to sail these waters. The first documented shipwreck on the Goodwin Sands was in 1298 and countless other ships will have been lost there since. The Sands are likely to hold the remains of the first traders from the Bronze age, Roman warships and cargo ships, Viking longboats and medieval merchant ships, ships sunk in war and ships wrecked on the sands themselves. It has been estimated that over 2000 ships have been wrecked here but only a few have ever been found. The Goodwins are also the last resting place of many airmen who were shot down during World War II so the remains of many aircraft are also there waiting to be found.

The Goodwins are known as the 'Ship Swallower' as shipwrecks often completely disappear beneath the sand as it shifts and moves with weather and tide. Huge sandbanks slowly move across the seabed covering and uncovering the remains of these ships, including the huge Royal Navy warship Stirling Castle lost in the Great Storm of 1703. This warship appeared from under a sandbank in 1979 in a remarkably good state of preservation and has been appearing and disappearing ever since.

Fig 1: The location of the Goodwin Sands off Kent, (red square)

Only a few of the many shipwrecks and aircraft lost on the Goodwin sands have ever been found. The ones that have been located are mostly large steel ships or older warships carrying iron cannon as both are easy to find. Only a few older, wooden ships or lightly-built aircraft have been found as they are more difficult to locate.

Surveys

Before any dredging work can be done the seabed has to be searched to show that there are no shipwrecks, aircraft or anything else of archaeological interest in the area. Underwater, the most interesting things to find are the hardest to detect such as Roman vessels or earlier, medieval merchant ships and aircraft, so it is essential that the search is carried out properly to ensure that the smallest objects of interest are detected.

Unfortunately the first search of the proposed Goodwins dredge area completed in 2015 did not use the geophysical survey instrument most likely to find the smallest wrecks, a magnetometer used for finding iron objects on or under the seabed. The first survey used side scan sonar to look for objects on the seabed, multibeam echo sounder to make a 3d map of the seabed and sub-bottom profiler to look for buried objects. The survey report mentioned problems with the side scan sonar data which was to provide the main search information as the data quality was poor. In addition, the sub-bottom profiler would not show small objects as the wrong instrument was used. The results of the survey were useless as the wrong methods and the wrong instruments had been used and the data they collected was too noisy.

In March 2017, 3H Consulting was approached by the Goodwin Sands SOS team to evaluate the marine geophysical method and results from the first survey. Further investigation discovered that inadequate survey methods were also employed on the Plymouth Disposal Site survey in 2013 and the London Gateway survey in 2010, yet all three surveys were signed off by Historic England, the regulatory authority. The results of this investigation by 3H Consulting Ltd. were published in the document The Suitability of Pre-Disturbance Geophysical Surveys for Underwater Cultural Heritage in England.

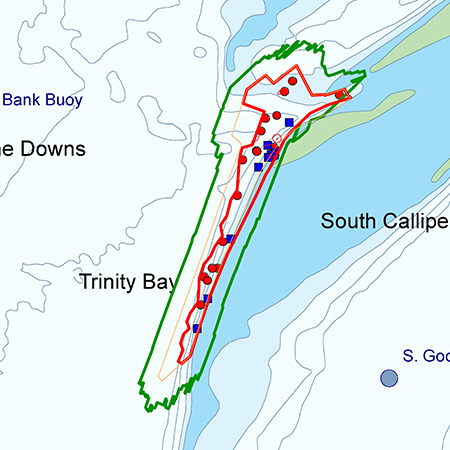

Subsequently, at the request of Historic England, a second survey of the proposed dredge area was done in 2017. This survey was carried out correctly and this time it included the magnetometer instrument missing from the first survey. The second survey detected 315 sites of archaeological interest within the dredge area of which 243 (77%) were detected by magnetometer. These 243 targets would have been missed and their associated archaeological sites destroyed had the second survey not been completed.

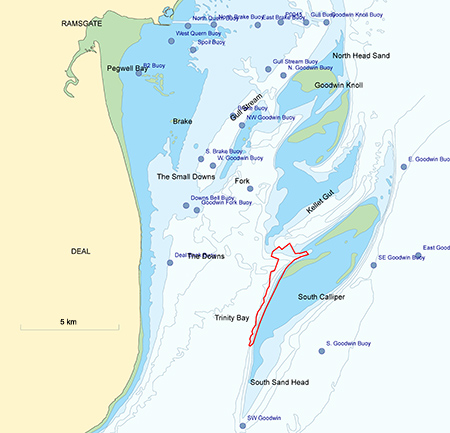

Due to the very large number of objects found during the second survey a smaller dredge area was proposed by Dover Harbour Board to avoid many of the targets detected. The problem remains that the smaller, revised dredge area contains many objects of archaeological interest as shown in Figure 4 (click on the image to see a larger version). The dredging Licence Decision Report states that the dredge zone has been altered to avoid any targets but this clearly is not the case.

Targets to be Investigated in the Dredge Area

As whatever lies on and under the seabed will be destroyed by dredging we are taking the unusual step of publishing the location of the historic material and encouraging divers to investigate these targets.

There are 24 targets in the proposed dredge area but 19 of them are small so are probably lost anchors or modern debris. However five targets require further and urgent investigation before they are destroyed.

These targets were originally misidentified when the second survey data was processed so the faint areas of debris around each one were missed. Re-analysis by 3H Consulting identified these five significant targets which are listed below and are described in more detail in the document Goodwin Sands: Archaeological Review of Geophysical Data, 3H Consulting Ltd.

We would appreciate receiving any information, photographs or video of whatever lies on the seabed at these locations so please get in touch by sending an email to pete@3HConsulting.com or to Goodwin Sands SOS. Details of anything lying within the 250m buffer zone around the refined dredge zone would also be welcomed.

Target List (WGS84)

1. WA ID 7028 (51° 13.275 N 001° 30.610 E)

A debris field covering an area 150m x 90m with discrete object 80-800kg at 7028 position, repeatable on multiple lines.

2. WA ID 7036 (51° 12.897 N 001° 30.271 E)

Area of magnetic disturbance covering an area 200m x 50m, aligned north-south which extends down to 51 12.777N 001 30.196E,

3. WA ID 7037 (51° 12.749 N 001° 30.467 E)

Target 7037 is surrounded by an area of magnetic disturbance covering an area 75m x 50m. This target and associated debris field may be associated with target 7309 and the 7311 group of buried targets 100m to the south.

4. WA ID 7041 (51° 11.847 N 001° 29.730 E)

Multiple small targets forming a debris field 30m x 50m surrounding a discrete 100-1000kg object.

Diving Information

Targets are in depth range 18 - 25m.

Nearest ports are Ramsgate and Dover - Link to tidal information for Ramsgate from the UKHO

Nearby boat slipways are listed on BoatLaunch web site

Diving is on a strictly volunteer basis to support Goodwin Sands SOS and no resources, funding or expenses are available. Many dive teams are contributing to this so please contact 3H Consulting before diving to get an update on the status of the targets, email: pete@3HConsulting.com

The Impact of Dredging on Shipwrecks

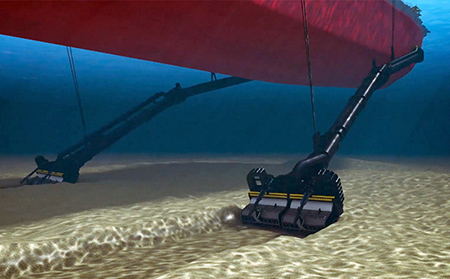

The dredging on the Goodwin Sands will be done using the kind of large ship called a suction dredger. A suction dredger trails two large dredge heads behind it which lie on the seabed and suck up seabed material. The sand and gravel is piped up to the surface and loaded into hoppers on board the ship. When the hoppers are full the dredger will sail to Dover and unload its cargo.

The large and heavy dredge heads are capable of continuously sucking up sand and gravel leaving a trench in the seabed behind them. The effect of this heavy gear being dragged over a wooden shipwreck or downed aircraft would be devastating - very little of the historic remains would survive intact on the seabed. The dredger would not even know it had dredged through a wreck or an aircraft gravesite, unless some part of the wreckage made its way up the dredge pipe and onto the ship, and someone was there to see it.

Fig 4: A suction dredger removes sand, gravel and old shipwrecks

Dover Harbour Board have stated they will have an on-board archaeologist present whenever the dredgers are at work. The dredging is planned to take place night and day over 4 months next year, so more than one experienced, qualified archaeologist will be required. The archaeologist will monitor a video link to the hopper head to ensure that no heritage asset has been sucked up from the seabed. However, by the time they spot anything, it will be too late as the damage will have already been done, the fragile ship or wreck destroyed and the in-situ relevance will have been lost.

References

- Holt P., 2017, The Suitability of Pre-Disturbance Geophysical Surveys for Underwater Cultural Heritage in England, 3H Consulting Ltd., Plymouth

- Holt P., 2017, Goodwin Sands: Archaeological Review of Geophysical Data, 3H Consulting Ltd., Plymouth

- Wessex Archaeology, 2016, Goodwin Sands: Archaeological Review of Geophysical Data, Report Ref 111510.01

- Wessex Archaeology, 2016, Goodwin Sands: Magnetometer Survey Specifications, ref 111511.01

- Wessex Archaeology, 2017a, Goodwin Sands: Archaeological Review of Geophysical Data (2017) Salisbury, unpubl rep 111511.02

- Wessex Archaeology, 2017b, Goodwin Sands Archaeological Review of Geophysical Data (2017) – Annex, unpubl rep.: 111511.03